To do or not to do an oil refinery for Uganda, over and above the pipeline, has been a major question for the country, but more importantly for the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC). At the centre of the answer to this question, lies the question of profitability and sustainability; two very viable questions, given the fate that has befallen many refineries on the African continent.

UNOC holds Uganda’s petroleum refining interests under its subsidiary, the Uganda Refinery Holdings Company Limited led by General Manager Dr. Micheal Mugerwa.

Other top executives at the lead of the refinery project include Ms Proscovia Nabbanja, UNOC Chief Executive Officer, Gilbert Kamuntu, the Chief Commercial Officer, and Peter Muliisa, Chief Legal and Corporate Affairs Officer.

These top executives will have to consider a refinery economic modelling analysis authored by two economic analysts, Mr Paul Bagabo and Thomas Scurfield at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), detailing five major factors with downside and upside scenarios including construction. cost; feedstock/ crude supply volume available; global oil price; product prices; and regional exports.

The analysis titled, ‘Uganda’s Oil Refinery: Gauging the Government’s Stake,’ shows the factors will have a significant impact on the refinery’s returns.

Concerns about the security of Uganda’s fuel supply have been at the heart of the government’s long pursuit of an oil refinery, set out as early as 2008 in the National Oil and Gas Policy.

All petroleum products consumed in Uganda are currently imported from overseas through the ports of Mombasa in Kenya and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

The refinery will have several benefits such as addressing Uganda’s problem with fuel supply, with current import routes from Kenyan and Tanzanian ports having suffered several disruptions.

The commitment to have an inland oil refinery in Uganda was advanced by Foster Wheeler Energy Limited Ltd from the United Kingdom, a consultancy firm contracted to conduct a feasibility study on building a refinery in Uganda in 2010/2011. The firm recommended that the development of a 60,000 barrels per day refinery was commercially viable with a Net Present Value (NPV) of USD 3.2 billion at a 10 per cent discount rate and an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of 33 per cent.

The government therefore estimates that it will collect about USD3.2 billion in total with an average of USD130 million a year assuming the refinery operates for about 25 years.

This translates to about 5 per cent of the revenue that the government expects to collect from the oil sector overall.

The internal rate of return is a metric used in financial analysis to estimate the profitability of potential investments.

Foster Wheeler Energy Limited Ltd also recommended the size and configuration of the refinery, location, financing options, and social and environmental assessment, among others.

The government also hopes that the refinery will stimulate the birth of a petrochemical industry, as part of the Kabalega Industrial Park in Hoima District, and will produce petrol, diesel, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), jet fuel, and heavy fuel oil (HFO). The petrol chemical industry will potentially produce a cheaper source of products such as fertilizers and plastics for Ugandans, and further improve the balance of payments through import substitution.

Additionally, the government expects 4,000-6,000 jobs to be created through the four years of building the refinery. Once the refinery is operating, it will only employ a small fraction of this number: the government expects around 650 people.

Any significant job creation therefore depends on the refinery procuring substantial amounts of local goods and services and on the success of related downstream industries.

The government plans to acquire a 40 per cent stake in the refinery, with private investors taking a 60 per cent stake. A United Arab Emirates-based company Alpha MBM Investments, linked to the Dubai Royal Family is set to become the lead partner in Uganda’s oil refinery project, a pivotal undertaking for the country.

Experts argue that the profitability of the refinery could be impacted by a range of uncertainties that affect refineries globally.

Mr Bagabo and his counterpart, Mr Scurfield, note that refinery economics are notoriously difficult to get right.

Many refineries in sub-Saharan Africa have, and are still struggling: often operating intermittently and below capacity and generating a loss.

For example, Nigeria’s refineries operated at an average of 15 per cent capacity between 2010 and 2018, and have been closed since for rehabilitation.

Ghana’s oil refinery with a 45,000 barrels per day processing capacity currently only operates at around 30,000 barrels per day and is not only struggling to secure funds for maintenance and repairs, but also to procure crude.

Niger’s refinery, constructed in 2011, has struggled to pay back its loans. Although Côte d’Ivoire’s refinery is viewed as one of the better performing in West Africa, it has also been facing financial challenges over the last decade.

In addition to these historical challenges, refineries are now facing new or increasing downside risks as the global energy transition accelerates. We delve into each of the factors discussed below in order of the size of their impact.

Construction cost

The government currently expects the refinery and supporting infrastructure to cost USD 4.5 billion to construct. Around USD 3.7 billion is likely to be required for the refinery, and around USD 0.8 billion for a product pipeline from the refinery to storage terminals in Kampala.

The main reason for the high cost of Uganda’s refinery is its relatively small size, which prevents economies of scale. However, building a larger refinery would probably not be to Uganda’s advantage either.

A larger refinery would be able to benefit from economies of scale but would face crude supply challenges that could offset any improvement in its economics.

As is often the case with large infrastructure projects, the refinery may suffer from cost overruns.

The estimated cost has already increased by about 12.5 percent, from USD 4 billion to USD 4.5 billion. This cost may rise further still.

An industry study of refinery projects across the world in 2014 found that they were, on average 69 per cent over budget. Therefore, even if no other downside risks materialise, the refinery still generates a low return merely by replicating the experience of most other refineries.

Even this significant overrun may be an underestimation of the risk. The cost of Nigeria’s Dangote refinery is now 111 per cent more than initially expected, rising from USD 9 billion to USD 19 billion.

However, the NRGI modelling suggests that the refinery’s high construction costs are likely to be offset by its access to reasonably cheap crude and its ability to sell its products at relatively high prices.

Given the high cost of transporting crude exports to the coast through the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (around USD 13 per barrel), the refinery will get its feedstock at a significant discount.

The government is planning for the refinery to sell its products at a price based on import parity. Uganda’s petroleum products market is deregulated. As the Petroleum Supply Act 2003 stipulates, prices are set by the market rather than the government. The refinery can therefore price its products at only slightly less than the import price and still undercut any import competition.

Given that import prices include transport costs from Mombasa to Kampala of around USD 7 per barrel, the refinery promoters believe it can achieve a reasonable profit margin.

Product pricing and demand for petroleum products

Uganda’s current arrangement of leaving petroleum product pricing to the market is important for the refinery’s profitability. This arrangement makes it more likely that it can pass higher costs on to consumers.

However, discussions with various Ugandan stakeholders suggest that oil production might result in citizen pressure on the government to make petroleum products cheaper. This is unsurprising. All African countries with a refinery, except for Ghana, subsidise petroleum product prices.

NGRI in their report modelled a downside scenario in which the government caps the fuel price at which the refinery can sell its products at 10 per cent less than the baseline.

The upside scenario has the refinery selling the finished product at a price that is 10 per cent higher than the baseline price.

The optimal size of a refinery is also determined by the characteristics of the markets in which it intends to sell its products and the competition it faces in these markets.

Uganda’s demand for petroleum products is growing quickly with an average daily consumption of 6.5 million litres of fuel per day.

The country also imports between 190 and 230 million litres of petroleum products per month mainly from the Arab Gulf with major refineries in Saudi Arabia, Dubai, India and other far-flung markets such as Malaysia, the Mediterranean, and the Italian belt.

In 2021, the country consumed the equivalent of 41,000 barrels per day in 2021, with petrol and diesel consumption by the transport sector accounting for about 85 per cent.

Some projections of future Ugandan demand for petroleum products are only on the rise which are included in the Energy Transition Plan that was released in December 2023.

Feedstock volumes are available.

The government through a Crude Supplier’s Agreement with the major oil companies – Total and CNOOC- is expected to secure the necessary feedstock of 60,000 barrels of crude oil per day required for the refinery.

However, Mr Bagabo points out that the government may not be able to secure a larger volume of crude oil for refinery operations as it is likely to harm the profitability of the crude oil exports through the East African Crude Oil Pipeline which has already agreed export volumes and the pipeline is already under construction.

The current uncertainty about when the refinery may start operations is also likely to affect and eventually reduce the available crude oil for its operations.

Experts at NRGI in their economic modelling suggest that Total and CNOOC may also end production from the Lake Albert project earlier than expected if the global energy transition results in prices falling below their operating costs.

Rystad, a Norway-based independent energy research and business intelligence firm estimates that the Lake Albert oil project will produce only 91 percent of its 1.4 billion recoverable reserves if the world achieves net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

On the upside, the refinery could benefit from getting more crude oil supply from its operations from the new exploration projects expected to add more reserves of crude oil, if successful. However, whether or when other such projects advance to oil production remains uncertain.

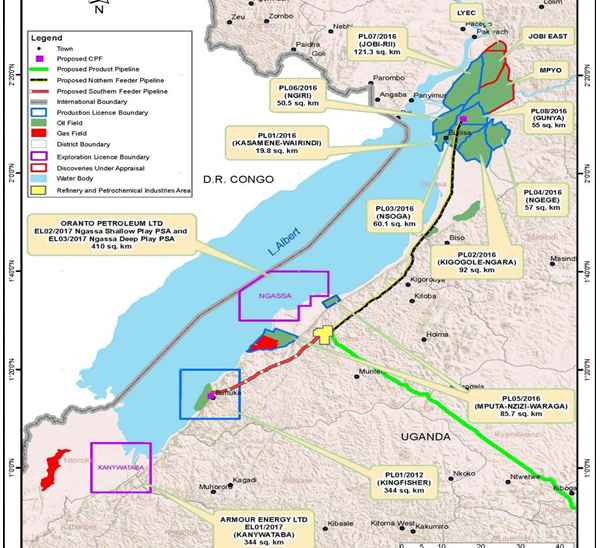

Data shows 60 percent of Uganda is unexplored and there has been a high success rate in areas that have been explored. Exploration plans are advancing in several other blocks, such as Ngassa, Kanywataba and Turaco within the Albertine Graben.

It remains to be seen which projects will advance to oil production, particularly given the uncertainty generated by the global energy transition. Nevertheless, the average project globally takes seven and a half years to get from discovery to production.

Regional exports

Uganda’s refinery will have to export any production that the domestic market does not consume. Being located inland, it will supply its landlocked neighbours without much competition unless other inland refineries are built in the vicinity.

Uganda’s most likely export customers include Burundi, eastern Democratic of the Congo (DRC)and Rwanda. Like Uganda, these countries import most of their petroleum products via Mombasa and Dar-es-Salaam. The routes are thousands of kilometres long which increases final sales prices.

As the refinery will be closer than the major ports, the suggestion is that it should be able to undercut current import sources and offer cheaper products to these countries. South Sudan has been identified as another market for Uganda’s refinery, however, this will entirely depend on how South Sudan’s refining ambitions develop.

Until recently, South Sudan also imported most of its products via Mombasa. However, a 10,000-barrel-per-day refinery began operations in 2021. The South Sudan government is planning other refineries, to supply both the domestic and regional markets.

There’s currently little information about these planned refineries in the public domain, so it is difficult to determine their prospects or what they may produce.

However, the key highlight is there’s a possibility that Ugandan exports may face competition even in inland markets.

Greater competition is envisaged to come from its coastal neighbours of Kenya and Tanzania, given their accessibility to overseas refineries from the Middle and India. It might be particularly challenging to sell liquefied petroleum gas given Tanzania and Kenya have LPG ambitions of their own. Tanzania is constructing its own LPG facilities.

The refinery may therefore supply western Kenya and northern Tanzania. However, even there, experts suggest that it may need to offer lower prices than it offers to its landlocked neighbours.

Global oil prices

Crude oil and petroleum product prices are the two largest factors that affect a refinery’s profits, and therefore any changes in the cost of crude oil can have a significant effect on profitability.

The economic modelling suggests that depending on the pace at which the world moves from fossil fuels to cleaner energies, the global oil price could be less or more favourable than the average USD 54 per barrel assumed as the baseline.

Many analysts and oil companies have been revising their long-term oil price assumptions downward. While a lower price will reduce the refinery’s crude supply costs, it is likely to reduce its sales revenues even more. The global oil price affects both the refinery’s costs and revenues, though not equally. A lower global price will likely reduce the refinery’s profitability.

The global energy transition is expected to result in a structural decline in the oil market in the next few decades. The pace of this transition is uncertain. However, even before governments unanimously agreed at COP28 to transition away from fossil fuels, the transition is already accelerating.

However, if the world achieves net zero carbon emissions by 2050 to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5C, the impact on demand expected by the International Energy Agency (IEA) could lead to an average price of USD 16 per barrel between 2025 and 2050 as a downside scenario.

The upside scenario has an average price of USD 94 per barrel during this period, in line with the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) demand projections.

This price rise results from OPEC’s expectation that oil demand will, in contrast to recent signs, continue gradually growing over the next three decades and that oil will become increasingly expensive to extract as cheap sources are exhausted.

However, OPEC’s price projections are significantly higher even than the IEA’s Stated Policies Scenario, in which governments only implement policies already in place or currently being developed.

Uganda National Oil Company Position

Peter Muliisa, the UNOC Chief Legal and Corporate Affairs Officer says that for any large project such as the oil refinery, a lot of value engineering is done to ensure that the construction cost is managed and maintained at what is expected, or less, and delivered on time.

But Muliisa admits things can change, “You can assume the prices of steel, and they change upwards or downwards, or you can assume financing to be easy and it doesn’t turn out to be easy.”

He adds, “But there’s always a mitigation for those assumptions, so the data that shows that about 25 per cent of major projects do suffer cost overruns, also that tells you that the 75 per cent are delivered at the estimated cost or less.”

On the idea of economies of scale, Muliisa says, each project has its own advantages, and in this case, Uganda’s advantage is that it has an inland refinery with a captive source of crude oil compared to other refineries across the world located at the sea shores.

On pricing, Muliisa explains that the refinery pricing mechanism is designed to compete at the level of the international market price using netback pricing- a concept used in the oil and gas industry to assess the profitability and efficiency of a company based on the price, production, transportation, and selling of their products.

This means Uganda has a cost advantage for its crude and refined petroleum value by knocking off the transportation margin of imported petroleum products.

Therefore, product pricing will largely be driven by supply and demand, and the global trading structure, considering that the project is private sector-led with an investor and government mix participation.

“If the government has to impose a price, then it has to enter a subsidy structure and subsidies have not worked in any country in the world, and they’re disruptive,” he says.

Muliisa adds that the refinery, in all agreements, shall be given priority to get a share of the crude oil supply for its operations.

The government has also embarked on an aggressive exploration campaign to secure more crude oil.

On global oil prices, Muliisa notes that the volatility of crude oil prices is nothing new, and has partly been influenced by climate change.

“Volatility is considered in every economic model, so you have to look at the historical performance and based on that, you consider an average reasonable price to work with and factor in other elements of major shocks,” Muliisa says.

However, he remains optimistic that petroleum will remain a significant energy source, accounting for about 44 per cent of the global energy mix and the pace of investment and technology cannot be displaced.

“The carefulness with which entities invest in upstream projects shows that chances are high the oil prices will be high,” Muliisa says.

SDG Activation Day in Uganda highlights private sector’s role in advancing 2030 Agenda

SDG Activation Day in Uganda highlights private sector’s role in advancing 2030 Agenda