Uganda’s central bank, the Bank of Uganda, has its work cut out in implementing its domestic gold purchase programme that was launched in July this year.

The Bank’s gold programme has been well received in many quarters, especially among miners, civil society and policymakers.

Many are hopeful that the programme could help streamline and bring sanity to a sector that remains beleaguered by gold smuggling, unscrupulous middlemen, unfair pricing mechanisms and poor regulation.

The Bank of Uganda communications team, through an email statement sent to the CEO East Africa Magazine, noted that the central bank is in the process of operationalising the pilot domestic gold purchase programme after visiting miners in the Districts of Buhweju, Kassanda/Mubende and Busia, and held workshops to address queries about the program.

“The Bank is currently pre-qualifying suppliers and working on other internal arrangements to start purchases as soon as possible,” a statement from the Bank reads in part.

In August 2024, the Bank established an operational framework detailing the approach, pricing, and other guidelines for the program.

For the uninitiated, the programme is aimed at building the country’s foreign reserves and minimising associated risks on reserve investments in the international financial markets.

It will involve purchasing gold directly from the artisanal and small-scale miners, which also, in part, is to support the miners’ livelihoods with a positive spill-over effect on other sectors of the economy. The Bank, in consultation with relevant key stakeholders, first released the details of the gold purchase program in its much anticipated State of the Economy report, which presents economic developments in Uganda for the three months to May 2024.

The Bank also expects the program to support the government’s ongoing value addition to minerals and the import substitution strategy by reducing the imports of raw gold into the country.

In an interview with the BBC in July, Bank of Uganda Deputy Governor Micheal Atingi- Ego, further explained that the decision was based on operational challenges that the central bank has been facing, given the increased diversity, frequency and shocks that have adversely affected the bank’s capacity to fulfil its mandate.

“Some of these shocks have resulted in the dwindling of our reserves because there has been a light build-up of external debt and serving, the rise in import of goods and services, a sustained drop in capital flows, and significant pressures on the exchange rate,” Atingi- Ego told the BBC, noting that the bank was looking at mitigating the decline of the forex reserves by utilising the available natural resources.

Mr Atingi-Ego noted that the price of gold would be determined by several factors, such as the purity levels of the gold and also based on the date of delivery by the supplier required to notify the bank about the quantity of gold to be supplied.

“The price shall be determined using reputable international gold trading platforms such as the Bloomberg Composite Gold Index, and the price will be translated into Uganda Shillings,” Atingi-Ego said.

Karamoja gold mines

To understand the nature of gold mining and trade in Uganda, one has to take a field trip to the flatlands of Rupa Sub County in Moroto District in the Karamoja sub-region in North Eastern Uganda.

The Rupa flatlands provide a good scenic view of Mount Morot, but underneath these flatlands lie mineral assets that have attracted thousands to the area in search of wealth.

Karamoja sub-region, which is almost the size of Rwanda at 27,528 square kilometres, is rich in two assets: mineral resources such as tin, gold, copper, cobalt, marble, limestone, graphite, and uranium and the cultural diversity of her people consisting of tribes straddling the borders of Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan.

Although the area’s huge mineral deposits have the potential to revitalise the local economy, there’s yet full economic realisation from the region’s natural resources.

Nevertheless, mining is still contributing to local revenue and supporting the livelihoods of artisanal miners.

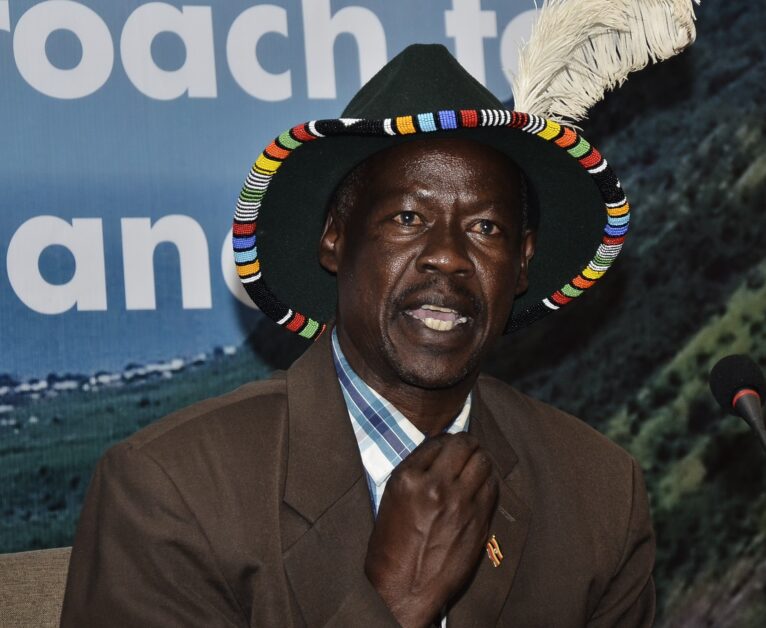

Simon Nangiro, an artisanal miner and chairperson of the Karamoja Miners Association.

Nangiro, in a close watch of the changing events, can relate to the proverbial Old Benjamin’s character in George Orwell’s book, ‘The Animal Farm’, who used to utter nothing beyond the cryptic remark ‘donkeys live a long time.’

Since the turn of the decade in 2010, Nangiro has lost count of the small-scale miners and middlemen exploring the sub-region in search of the precious gold.

Nangiro is one of the hopefuls that the Bank of Uganda project could change the lives of miners in his subregion.

“One challenge we have been facing as miners is not being sure of what market we are dealing with. Secondly, the element of middlemen; so when it comes to a government institution like that, we welcome the idea because we’re sure about the entity we’re dealing with,” Nangiro says.

He notes that originally, some gold buyers, who were mostly middlemen, have been fleecing artisanal miners, claiming the gold sold to them was a fake product. But his hope is that it is likely to change with the Bank of Uganda gold purchase programme.

“We should have locations where we deliver this gold. It should not be inconveniencing for the artisanal miners because most of our miners are in rural settings, and then also we need testing kits to know the purity and quality of the gold,” Mr Nangiro told the CEO East Africa Magazine.

Nangiro says pricing is still a challenge in the informal gold trade chain, with most of the gold prices based on demand and supply, or bargaining power. A gram of gold in some Karamoja mines is priced between UGX 200,000 (USD 54) and UGX 300,000 (USD 82).

“The Bank of Uganda needs a proper pricing channel. Most of the buyers dominating the gold trade are Congolese and Rwandans, but if the Bank of Uganda is coming to purchase our gold, we shall know the price will be favourable,” Nangiro expresses optimism.

Gold: A precious resource

Karamoja is a major contributor to Uganda’s gold production, with other mining areas spread across the different regions in the country.

A Uganda Investment Authority (UIA) memo on Uganda’s mining sector shows gold is widely distributed in Uganda but is mined from only a few areas and districts, such as Bushenyi, Kabale, Kisoro, Mubende, Moroto and Hoima.

According to the UIA, most gold production has been by small producers who include licensed small-scale miners and artisanal miners.

Currently, gold and cobalt account for over 95% of all minerals exports from Uganda. The escalating values of gold, along with the accompanying investor interest, have grown in the recent past and, in all likelihood, will continue.

As noted by Barrick Gold, a Canadian-based mining company with business interests in Uganda, the supply of gold continues to lag demand, making the exploration and development of new gold resource sources imperative, and Uganda will reap big from these developments.

Gold mining in Uganda is predominantly informal. An estimated 190,000 Ugandans employed by the artisanal and small-scale mining sector in Uganda produce about 90% of all minerals, including gold. Before a large-scale eviction in 2017, it was estimated that about 40,000 people were mining for gold in Mubende (in the central region of the country) alone.

According to Uganda’s National Action Plan for artisanal and small-scale miners, gold production by small-scale miners in Uganda amounts to 7,081 kilogrammes of gold per year, which accounts for more than 90% of gold production.

Uganda’s central region is the highest gold producer with over 2,500kg annually (36%), followed by Eastern with 1,700kg (25%) and Karamoja with 1,400 kg (21%). Ankole and Kigezi regions produce 1,183kg (17%) and 91kg (1%) of gold, respectively. These statistics are bound to change over time with more gold discoveries in Eastern Uganda.

Uganda has also attracted private investments in gold refineries to improve its export earnings from the precious resource.

D.R Congo gold smuggling connection

But even as the Bank of Uganda plans to roll out its ambitious gold plans, it will have to deal with Uganda’s hidden gold skulls.

On 29th November 2023, Uganda, through the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, joined other Eastern and Southern African countries to launch the issuance of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) Certificate for designated minerals in Uganda.

These minerals include Tin, Tungsten, Tantalum and gold. The certificate was launched by Hon. Peter Lokeris, the former Minister of State, in an event held at the lakeside Speke Resort Munyonyo, and, in attendance was the Ministry of Energy Permanent Secretary, Ms Irene Batebe.

The ICGLR certificate was named after the International Conference for the Great Lakes region held in December 2010 in Lusaka, Zambia.

The certificate is one of the six tools of the regional initiative to fight against the illegal exploitation of natural resources in the Great Lakes region that was signed into force by the heads of ICGLR member states.

It serves as an assurance to mineral buyers that a shipment of minerals is free from conflict and that it meets all other ICGLR standards.

The other five tools include harmonisation of national laws and domestication of the protocol regional mineral database, formalisation of artisanal mining sector, Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and whistle-blowing mechanism.

So far, the certificate is applicable in other countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania.

However, the issuance of the ICGLR certificate is not a problem; the problem is that even after its issuance, there have been continuous reports on Kampala, Uganda’s capital city, being a transit route for illegally imported gold from the gold mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

According to figures from the Bank of Uganda, the value of Uganda’s gold exports nearly quadrupled, growing by 2.7 times, from USD1.135 billion in FY2022/23 to USD3.092 billion in FY2023/24.

The actual statistical details of how or where all the gold is sourced from have remained scanty except for the known mining regions in the country.

It is for this reason that the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime reported in 2021 that Uganda’s domestic production remains dwarfed by the amount of gold smuggled into the country from its neighbours, primarily the DR Congo and South Sudan.

As one gold dealer is quoted saying, “Most of the gold we get here [in Uganda] is in transit’, and almost 95% of it is illicit. Once the smuggled gold arrives in Uganda, dealers claim it is of Ugandan origin, supported by fraudulent documentation which the authorities find difficult to disprove.”

Uganda is reported to provide an attractive market environment for illicit gold due to the ease with which gold can be moved and traded and because of the presence of many well-resourced buyers purchasing gold at competitive prices.

Low export royalties also contribute to a larger profit margin. Insecurity in both eastern DRC and South Sudan also makes Uganda an attractive destination for smuggled gold from those countries.

A letter dated 31st May 2024 from the UN Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the UN Security Council, indicates that the weakness of border controls between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Uganda facilitates gold trafficking.

In January 2024, the UN Group visited the town of Mahagi in Ituri, a transit hub for individuals transporting gold from Bunia to Uganda. DRC security services reported that hundreds of trafficking routes from Mahagi territory leading to Uganda were outside their effective control.

Several sources confirmed that they used these routes, for example, to sell gold to traders based in Paidha town in the West Nile sub-region in Uganda.

Several sources indicated to the UN that most Kampala-based gold actors knowingly purchased gold smuggled from the DRC.

The company Metal Testing and Smelting Co. Ltd. and its directors were consistently cited in the UN report as having purchased gold extracted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Metal Testing is one of the leading exporters of gold in Kampala. The company is owned by Himat Dhedi, also known as Patel Himat.

Multiple sources, including DRC officials and judiciary sources, informed the Group of a transaction between the company’s directors and a Bukavu-based gold provider, in which the Kampala-based Metal Testing company pre-financed the supply of gold. This deal between Dhedi and the smuggler lasted until mid-2023.

Three Kampala-based individuals also described how, on several occasions in 2022 and 2023, Metal Testing managers sent them to Arua on the Uganda-DRC border to purchase gold from smugglers.

The individuals’ role was limited to checking the gold’s authenticity and transferring the money provided, either in cash or through a bank transfer. The individuals reported multiple weekly operations worth 20 kilogrammes of gold each.

Concerning natural resources and finance, the UN Group of Experts indicate that armed groups and criminal networks, including national security officers, have continued to use gold and taxation as sources of illegal revenue.

The Group noted that in Congo areas of Bunia and Bukavu, gold sourced in high-risk and conflict areas was exported illegally to Uganda.

In another UN report published in 2018, provincial mining authorities in Ituri told the Group that Bunia was still an important gold trading centre, consistent with the Group’s current findings.

The UN Group interviewed 10 Bunia-based gold traders — who informed the Group that gold traded in Bunia was mainly sourced from mining sites in Mambasa, Djugu and Irumu territories in Ituri Province.

The Group noted that most of the mining sites in those areas were not validated. As a result, most of the gold traded in Bunia was illegally sourced and had the potential to contaminate supply chains at its final destination in Uganda and the United Arab Emirates.

In the course of its investigations, two Ugandan nationals working for two airlines operating from Entebbe International Airport informed the UN Group that they are not requested to check gold in hand luggage.

In the course of its current mandate, the Group held discussions with senior officials of eight airlines operating in and out of the Great Lakes region, who said that their primary role in checking passengers was to make sure no one was carrying anything that could jeopardise the security of the plane, a policy focusing almost entirely on weapons and explosives.

The Group is of the view that gold transported on commercial aeroplanes should not be banned as it represents a key form of export for responsible artisanal and small-scale mining activity that observes the requisite due diligence guidelines.

However, there is a need to address the loopholes related to the illegal transportation of gold carried in hand luggage on commercial aeroplanes.

The Ghana gold purchase experience

Elsewhere across Africa, the gold purchase programme provides a mixed bag of experience and lessons for Uganda.

In 2022, Dr Mahamudu Bawumia, Ghana’s former vice president and central banker, announced that the country had engaged key stakeholders, including the Ghana Chamber of Mines, to draw a roadmap for the implementation of the Bank of Ghana’s gold purchase programme across the industry.

Ghana, which is a large gold producer, aimed at shoring up the foreign exchange reserves of the Bank of Ghana by purchasing a portion of the output of the gold mining companies continuously at world market prices, with payments made in Ghana cedis, the country’s official currency.

On September 27th, 2024, Dr Ernest Addison, the Bank of Ghana Governor, launched the Ghana gold Coin (GGC), a development which he said marked a significant milestone in the Bank of Ghana’s history.

“This initiative is a testament to our unwavering commitment to deepen financial markets by offering other avenues for savers to invest. It also serves as a significant reminder of our nation’s rich gold heritage,” Dr Addison said.

The Ghana gold Coin issuance is expected to mop up extra cedi liquidity in the banking sector and supplement the use of the Bank of Ghana Bills and overnight depo for open market operations.

Dr. Addison also noted that, the Ghana gold coin would give additional avenue to savers resident in Ghana to invest and reap the benefits from the Bank of Ghana’s domestic gold purchase program.

“Gold has shown remarkable resilience as a financial asset and can serve as a natural hedge during periods of economic turbulence,” he said.

Early this year, Dr Addison was quoted by GhanaWeb, an online media outlet, noting that the implementation of the Domestic Gold Purchase programme had significantly improved the country’s local currency since its inception.

Dr Addison told GhanaWeb that the gold reserves programme had raised over USD 1 billion, compared with IMF’s USD 600 million disbursements since the start of 2023.

Leandro Medina, the IMF Resident Representative in Ghana, wrote in January 2024 that two years ago, Ghana suffered from elevated fiscal deficits and public debt levels, together with the combined effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine, and global monetary policy tightening which triggered a drop in international investor confidence in Ghana, resulting in a loss of international market access.

This generated increasing pressures on domestic financing, with the government turning to monetary financing by the central bank, which fed into declining international reserves, currency depreciation, and accelerating inflation.

However, by July 2024, an IMF country report on Ghana showed how Ghana’s gross international reserves had significantly outperformed expectations, reaching US$3.7 billion at end of 2023, compared to an original estimate of US$2.4 billion. The main driver of this accumulation was the Bank of Ghana’s large gold purchases, accounting for about US$1.5 of the US$2.2 billion total reserves increase in 2023.

The IMF also noted whereas Ghana’s international investment position has improved as a result of the gold purchase programme; the West African country’s Balance of Payment position does not reflect the improvement unless the gold is sold/exchanged on international markets, and thus recorded as export.

However, some critics are in disagreement with the gold programme, noting that it has disrupted the business for Ghana citizens.

Benjamin Boakye, the Africa Centre for Energy Policy (ACEP) Executive Director, told the CEO East Africa Magazine that Ghana’s gold programme has disrupted the whole value chain of gold, leading to the smuggling of the precious mineral out of the country, let alone making some gold buyers redundant.

Boakye leads ACEP based in Ghana, which is a research and policy think tank in Africa’s extractive governance space.

“There are many people who were gold buyers, and they no longer have jobs, and officially, they cannot export gold anymore. The few buyers of gold in the country are politically aligned. Some of the gold buyers used to fund the operations of the small-scale miners, but when you take them off, they go underground to find gold and export it,” Boakye explains.

The silver lining

In spite of the lingering challenges, experts in the financial markets have welcomed the Bank of Uganda’s move as a step in the right direction.

Nobert Kiiza, a Public Education Officer with Uganda’s Capital Markets Authority, in his analysis, says gold has remained a precious metal that has seen extraordinary gains in 2024. An ounce of the precious metal was trading at around USD 2500 (UGX 9.2 million) as of August 2024.

Kiiza notes that the enormous rally of this safe haven asset has been driven by numerous factors such as heightened geopolitical tensions from the Middle East, growing fears of the stability of the United States dollar amidst quickly rising debt position, and global rate cuts from central banks, among others.

He adds that the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) implemented Basel III in January 2023, which saw gold reclassified as a Tier 1 asset from Tier 3.

This move has allowed gold to become attractive, especially as a reserve by banks. This development underpinned the sharp uptick in central bank gold purchases as reserves over 2023 and the first half of 2024. The new valuation to value gold using marking its price to market has made it more volatile.

The policy shift by the world’s largest economy has allowed demand into the central bank since late 2022. gold’s 2024 year-to-date performance against the US dollar is more than 20%, making it one of the best-performing assets so far this year.

The demand for gold by central banks is largely premised on the need for a long-term store of value or inflation hedge. Other reasons include an effective portfolio diversifier, historical positioning and being a highly liquid asset.

Quoting data from the World Gold Council, Kiiza says that central banks added 459 tonnes of gold in Quarter 3 of 2022, the highest on record. In Quarter 1 of 2024, up to 300 tonnes were added by central banks.

Kiiza says with the Bank of Uganda adding gold to its portfolio; it would have more US Dollars in value for gold held over a period. The upward trend of gold in earlier years also defended their investment position.

“One of the most reliable alternative assets, such as gold, offers a safe haven during turmoil in the markets when volatility erodes traditional assets’ value. Gold acts as a safe haven, but besides this, gold has its merits,” he says.

Similarly, Joram Ongura, Founder of Amioo Capital Limited, notes that investing in gold is mostly attractive for its diversification benefits; this is a key strategy in managing risk and gold reserves act as a great diversification tool.

“Historically, when stocks and fixed income instruments underperform, especially during times of high inflation and recession, gold often performs better than traditional assets,” Mr Ongura says.

Ongura provides a case in point: in 2020, when markets dipped across the globe due to the impact of COVID-19, for example, the Nairobi Stock Market 20 Index plummeted 29%. The index is considered a barometer of the overall performance of the top 20 companies on Nairobi Stock Exchange, and provides a benchmark for investors to measure the performance of their portfolios.

However, in comparison within the same period, the Absa New Gold Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) price unit in Kenya recorded gains of about 34% to UGX 55,963 (KES 1,975) from UGX 41,654 (KES 1,470) within the period of January to December 2020.

This means if one had invested UGX 10 million in 2020 on the Absa New Gold ETF, by 2021, they would have made a return of 34.3%, which is 13.43 million.

The Absa New Gold ETF is listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) which enables investors to invest in an instrument which tracks the price of Gold Bullion. Price movement of the ETF is determined by the price movement of gold.

Ongura adds that gold is highly liquid, it can easily be converted to cash, which means one can cash out easily, whether in physical bullion or digital form.

“Investing in gold provides relative protection against depreciation/ devaluation since the value of gold is independent of Uganda’s economic situation. Hence, the move by the Bank of Uganda to invest in gold is an excellent move as the above benefit would appeal to Ugandans,” Ongura concludes.

Taking precautionary measures

Uganda’s mining sector still operates in a siloed approach, and this could prove a challenge for the Bank of Uganda in obtaining gold. However, there’s hope.

Irene Batebe, the Ministry of Energy and Minerals Permanent Secretary, told the CEO East Africa Magazine that, the government is offering support to the artisanal and small-scale miners by setting up beneficiation centres, which are value-addition centres in the districts of Ntungamo and Fortportal.

“The small-scale miners can add some value so that they can earn more when they are selling to the next buyer. Critically, we’re pushing for mineral certification. Minerals, if not well monitored, may end into illicit mineral trading as well as fuel conflict,” she said.

While at the recent 13th Mineral Wealth Conference organised by the Uganda Chamber of Mines, Hon. Ruth Nankabirwa, the Minister of Energy and Mineral Development (MEMD), says the government is subsequently embarking on putting in place regulations to support national content development with a plan to undertake a Baseline Survey (Study) to establish the current status of national participation and understand the available opportunities for Ugandans.

“We continue to register artisanal miners under our biometric registration project, and to date, we have registered over 5,000 artisanal and small-scale miners. Registration will greatly advance their formalisation and licensing to work in the established artisanal mining zones,” she says.

Letters to My Younger Self: Robinah Siima — “Success Is Quieter, But Richer”

Letters to My Younger Self: Robinah Siima — “Success Is Quieter, But Richer”